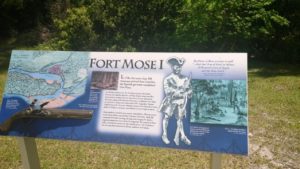

Across a swampy marshland in America’s oldest settlement, St. Augustine, Florida, lies all that is left of Fort Mose — a wild island accessible only by boat. Nearly three centuries prior, Fort Mose stood as the original American melting pot.

Established by the Spanish in 1738 as the first free Black settlement as a way to undermine the slave economy of the English colonies, Fort Mose was the safe haven for Black men, women and children who had escaped slavery on the Underground Railroad to the south. Blacks, Hispanics and Indigenous Americans all lived together within its bastions.

I learned of Fort Mose for the first time while preparing for an interview with acclaimed historian, professor and documentary filmmaker Dr. Henry Louis Gates regarding his Peabody Award-winning documentary series, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, and knew I had to go there and experience that place for myself.

Thanks to the St. Augustine tourism board, I was able to visit the quaint, beach-side city as it celebrates its 450th anniversary — that’s 42 years before Jamestown’s founding in Virginia. Historian and playwright James Bullock graciously escorted me through the now-closed exhibit Journey: 450 Years of the African American Experience, where homage was paid to the many Africans who were integral to St. Augustine’s founding, including Juan Garrido, the first-known African to set foot on what would become America, a free West African conquistador who traveled with famed explorer Juan Ponce de Leon on a Spanish expedition.

Nearly 200 years after St. Augustine’s founding, Fort Mose was built, and while it was not likely a Utopian society, the need for community among diverse people in order to survive attacks was strong enough to bind the people together. It was short-lived. Spain ceded Florida to England and the people of Fort Mose took up new residence in Cuba. But Black history in St. Augustine was far from over.

It doesn’t escape me that the oldest settlement in America became one of the most iconic sites of blatant racism in the nation during the Civil Rights Movement. Black Heritage Tour guide Bernadette Reeves took me through the streets of old St. Augustine, to the still-standing Woolworth’s building where the St. Augustine Four sat at the counter in protest. Now owned by Wells Fargo, the King Street building, with the letter-tracings of its predecessor still present on the outside, has re-installed the famous counter inside the bank in homage to the protesters’ bravery.

Reeves also showed me the house where Martin Luther King stayed while he was organizing in St. Augustine and the Andrew Young Crossing, a renamed street and monument to the famed activist who was severely beaten during a march on the ironically named Plaza de la Constitución,

Even on my own, with every step I took, I was running into my history. The first time I walked up the stairs to get to my hotel suite at the Bayfront Hilton, I had no idea I was also retreading the very steps Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested on for protesting segregation at what was formerly known as the Monson Motor Lodge.

Monson’s pool — now an unused monument — was the infamous spot where the white lodge owner, Jimmy Brock, poured acid into the pool where Black and Jewish protesters were swimming. A photo of that horrific event, coupled with news of the beating of protesters at the Plaza, circulated worldwide, causing enough widespread outrage and embarrassment for President Lyndon B. Johnson, that the stalled Civil Rights Act of 1964 was finally passed into law.

And still, so little has changed.

While waiting to board the 16th-century replica Spanish ship El Galeón on the docks of the Municipal Marina, I pondered how a city, which started with such promise, and a progressive fort built with such inclusive intention, could still yield the rotten fruit of the Plaza beatings and the Monson inhumanity. I still have no answer.

But I’ve found that living for the questions guarantees a well-spent life, and St. Augustine is full enough with the history, beauty, blood, sweat and tears of Black people to stir within you endless questions, and possibly even an answer.

In light of the protests that have sprung up around the country and the world demanding justice for Freddie Gray, an end to police brutality and a decree that Black Lives Matter, there is no better time to learn from the people of Fort Mose — the Africans, Indigenous Americans and Hispanics who, for a time, banded together in free community for their collective survival — and remember that another world was and still is possible.

Brooke Obie is a senior editor in New York and the author of an upcoming novel series.