Dr. Laurence Jones founded the school for poor Black people in the segregated South amid a culture of profound racism. Even the governor, James Vardaman, was a notorious white supremacist who did not want Blacks to get an education. Jones and his wife, however, did not cave in to the objectors.

White business owners in Ranking County, where Piney Woods sits, helped protect Jones and the school from the opposition. A white sawmill owner donated lumber, and Jones repaired the damaged sheep shed on the land donated by a former enslaved person.

Today, the school continues to produce countless bright young minds—a remarkable achievement considering its location in rural Mississippi, the struggle for aid, especially during the Great Depression, and the general substandard conditions of many schools that serve African-Americans in Mississippi and across the country.

Piney Woods has benefitted from Jones’ dogged determination and people who see the wonder of what he created. Jones, who died in 1975, raised money from people in the North, and when it began graduating scholars like Nobel Peace Prize nominee Randy Sandifer, it served as confirmation of its impact.

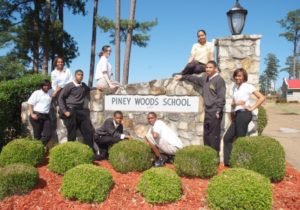

Indeed, Piney Woods, located about 20 miles south of Jackson, should be a model for all schools. It has blossomed into a challenging, college-prep vocational agriculture school for low-income African-American students in Mississippi and across the country. Its emphasis on discipline, effort and commitment challenges students, many of whom experience culture shock when they arrive, but later thrive.

Not graduating is not an option. And neither is not attending college, as all students are expected to get a higher education. There are 120 students at Piney Woods, a third of them from Mississippi. The rest come from 20 different states, Ethiopia and the Caribbean.

Private donations, foundations and scholarships help with the $23,000 annual tuition. Students work part-time on campus to offset the financial aid. Its president is Willie Crossley Jr., who graduated from Piney Woods 30 years ago. He went there to escape a rough neighborhood on the southside of Chicago. Crossley attended the University of Chicago and earned a master’s degree in education from Harvard and a law degree from the University of Virginia.

Crossley taught in Chicago’s public schools and later held prominent jobs as chief counsel for the Democratic National Committee and as a senior adviser in the Office of Civil Rights at the education department. He came on board last year.

“College is a huge focus,” Crossley said to The Atlantic, “and one that many of our kids aren’t able to realistically believe they can achieve—until they come into an environment where it’s not only realistic but it’s expected that they will, in fact, do that.”

Motivational quotes adorn the 2,000-acre boarding school, where students are up at 5:30 each morning and in bed by 10 p.m. In Jones’ autobiography, The Little Professor of Piney Woods, he wrote that on the first day of school in 1910, he told 100 students: “You have come here to seek freedom, not from the kind of slavery your parents endured, but from a slavery of ignorance of mind and awkwardness of body. You have come to educate your head, your hands, and your heart.”

That message has resounded within the campus for more than 10 decades. On a stone in a gazebo at the school is etched one of its credos: “Success Depends Upon Yourself.”

“I see this history like gold,” Maya Riddles, a 17-year-old junior from Atlanta told The Atlantic. “Stereotypically, people don’t see African Americans as being successful. Whereas, you come here, and there are a lot of successful African-American people here.”