In a lovely two-story house that’s still standing in Savannah, Ga., a meeting was held nearly 150 years ago today that essentially established the duplicitous nature of the relationship between African-Americans and the white power structure in the United States.

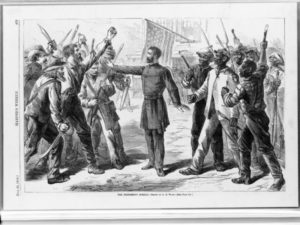

The meeting was between Union General William T. Sherman and a group of local Black leaders from Georgia. The purpose of the meeting was to determine the manner by which the newly freed Black people would live their lives in a country that still clearly saw them as no more than property.

At this fateful meeting, Gen. Sherman came to a decision that would result in Special Field Order 15, issued on Jan. 16, 1865, which stated the former enslaved people would be entitled to “a plot of not more than forty acres of tillable ground”—what popularly became known as “40 acres and a mule.”

In an upstairs room in this ornate Gothic mansion, known as the Green-Meldrim House, America actually established the framework for reparations for the millions of freed men and women in its midst. But that decree was to be short-lived.

Sherman stayed in the Green-Meldrim House in Savannah after his famously destructive march through Georgia, during which his troops were followed by thousands of freed slaves. He presented the city of Savannah to President Lincoln as a Christmas gift on Dec. 22, 1864.

With Secretary of War Edwin Stanton at his side, Sherman met with the local Black leaders, who were led by Rev. Garrison Frazier. Susan Arden-Joly, the preservationist and tour guide at the Green-Meldrim House, brought NPR on a tour through the house, up a winding staircase to the room where the group met.

Arden-Joly said Sherman and Stanton asked the group’s leader, the Rev. Garrison Frazier, a series of questions.

“Fourth question: State in what manner you would rather live, whether scattered among the whites, or in colonies by yourselves,” she read from Sherman’s memoirs.

Frazier’s answer was incredibly prophetic: “I would prefer to live by ourselves, for there is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over.”

Charles Elmore, a professor emeritus of humanities at Savannah State University, told NPR that Sherman and Stanton listened to Frazier and the others.

“The other men chose this eloquent, 67-year-old imposing Black man, who was well over 6 feet tall, to speak on their behalf,” Elmore says. “And he said essentially we want to be free from domination of white men, we want to be educated, and we want to own land.”

Four days later, Sherman signed Field Order 15, which set aside 400,000 acres of confiscated Confederate land on the for freed slaves. Sherman appointed Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton the task of dividing up the land. He was to give each family up to 40 acres—and some also received leftover Army mules, though that wasn’t in the decree.

But after Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson eventually reversed Sherman’s order, giving the land back to its former Confederate owners. There were many cases of law enforcement authorities forcibly removing African-Americans from land they had obtained through the decree.

“Once the passion of war was over, the idea of that kind of social experiment lost favor with a lot of people very quickly,” Elmore explains.

Vaughnette Goode-Walker, a writer who leads tours focused on Savannah’s black past, told NPR the entire saga represents one of the biggest “gotchas” in American history.

“‘Here, take this land—but we can’t really give it to you because it doesn’t belong to us; it belongs to the Confederates when they come back home.’ How confusing is that?”

After the reversal, many African-Americans with few options became sharecroppers, often working for former slaveholders. In effect, the saga set in motion the events that led the nation to become a place 150 years later where the average African-American family has very little personal wealth and considerable financial instability.

Imagine how different the lives of Black people in the U.S., and as a result the entire country, would be if hundreds of thousands of families had been able to claim and keep those 40 acres.