BY RUNOKO RASHIDI*

Great African men and women have played an important part in Roman history and culture from an exceptionally remote period. The distinguished writer Publius Terentius Afer (190-158 B.C.E.), for example, was the African who penned such immortal sentences as, “I am a man, and reckon nothing human is alien to me” and “While there is life, there’s hope.”

Terence was born in Carthage. In 158 B.C.E., Terence Afer departed on a journey to Greece to study the works of Greek writers. He never returned to Rome. Tradition says that Terence was drowned. His dramatic works influenced Cervantes, Shakespeare and Moliere, among others. Julius, Cicero and Horace used him as a model.

About 350 years after Terence, another outstanding African, Lucius Apuleius, wrote the classic work known as The Golden Ass, or Metamorphoses. Apuleius (ca. 124-180 C.E.) was born in Madaurus, Numidia (modern Algeria), on the North African coast and greedily imbibed Roman culture. His other works include On the God of Socrates. The Golden Ass is the only Latin novel that has survived in its entirety and ends with the hero, also named Lucius, being rescued by the goddess Isis — African goddess par excellence.

African Military Commanders

African soldiers, specifically identified as Moors, were actively recruited for Roman military service and were stationed in such places as Britain, France, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Poland and Romania. Many of these Africans rose to high rank. Lusius Quietus, for example, was one of Rome’s greatest generals and was named by Roman Emperor Trajan (98-117 C.E.) as his successor. Of purely African origin, Lusius is described as a “man of Moorish race and considered the ablest soldier in the Roman army.”

African Theologians and Saints

Among the most important theologians in early Christianity was Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus. Known as Tertullian, this African was the first of the church writers to make Latin the language of Christianity.

Tertullian was born into a rich family in Carthage in 170 C.E. He was the son of a centurion and was well-educated. He wrote Greek and Latin fluently and was well-trained in the school of rhetoric where Apuleius (another African) had been a student a generation earlier. Tertullian’s wife was a Christian, and he himself a convert. A man of fiery temperament and evangelical spirit, Tertullian became probably the most formidable defender of Christianity during his time.

Thaschus Caecilius Cyprianus, known as St. Cyprian, is called the greatest of the bishops of Carthage, the first African martyr-bishop and the man who, more than anyone, organized the African Church. His reputation was such that the Churches of Gaul and Spain appealed to him as an arbiter.

As an orator, Cyprian was such that only three years after becoming a Christian he, in 248 C.E., was elected bishop of Carthage. Sixty of Cyprian’s letters have survived as testament to his great intellectual gifts.

On Sept. 14, 258 C.E., St. Cyprian, amid great drama and after paying his executioner 25 gold pieces, and surrounded by a large crowd of Christians, was beheaded.

It is to St. Cyprian that we attribute the statement, “Whatever a man prefers to God, that he makes a god to himself.”

St. Augustine may have been the greatest theologian in the history of the Catholic Church. Augustine was the son of St. Monica, and largely because of her desires, he converted to Christianity in 386 C.E. In 395 C.E., he became bishop of Hippo, North Africa. His teaching on free will, original sin and the operation of God’s grace has been illuminated in numerous publications, particularly in his City of God. Augustine died during the siege of Hippo in 430 C.E.

African Martyrs

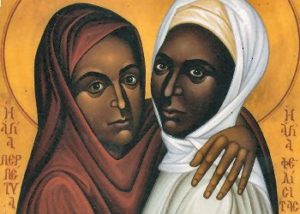

It was in 180 C.E. that the first known Christian martyrs of Africa were executed. One of the most famous and most outstanding acts of martyrdom, however, occurred in the year 203 C.E. and centers around two young, incredibly brave African women — Perpetua and Felicity. The account of their deaths, known as “The Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicity,” was so inspiring and popular in the early centuries that it was read during liturgies.

In the year 203 C.E., Perpetua made the decision to become a Christian, although she knew it could mean her death. Her father was frantic with worry and tried to talk her out of her decision. His motivation is understandable for at 22 years of age, this well-educated, high-spirited woman had every reason to want to live — including an infant son she was still nursing.

Perpetua was arrested with four others, including Felicity, the other African woman in our story. Perpetua was baptized before being taken to prison — a prison that was so crowded with people that the heat was suffocating. For Felicity, it was even worse as she suffered from the stifling heat, overcrowding and rough handling while being eight months pregnant.

The officers of the prison began to recognize the power and the faith and the strength and leadership of Perpetua, and the warden himself became a believer. There was a feast the day before the public spectacle so that the crowd could see the martyrs and make fun of them. But the martyrs turned this all around by laughing at the crowd for not being Christians and exhorting them to follow their example.

Bears, leopards and wild boars attacked the men, while the women were stripped to face a wild cow. When the assembled crowd, however, saw the two African young women, one of whom had obviously just given birth, milk running from her breasts, they were horrified and ashamed, and the two women were removed from the arena and clothed again. In spite of everything, however, Perpetua and Felicity were thrown roughly and brutally back into the arena. Regardless of her own pain and suffering though, Perpetua, filled with compassion and still thinking of others, went to help Felicity to her feet. The two then stood side-by-side, dignity intact, heads raised high as all of the martyrs assembled in the arena had their throats cut.

African Popes

There were at least three African popes at Rome. St. Victor I, the first we are aware of, became the first known African bishop of Rome in 189 C.E. and reigned until 199 C.E. Victor I, the first pope to write in Latin and the first pope known to have had dealings with the imperial household, is described as “the most forceful of the 2nd-century popes.”

St. Miltiades, a Black priest from Africa, was elected the 32nd pope after St. Peter in 311 C.E. Under Miltiades, after the issuance of an edict of tolerance signed by the Emperors Galerius, Licinius and Constantine, the great persecution of the Christians came to an end, and they were allowed to practice their religion in peace. St. Miltiades is regarded as a Christian martyr and died in early January 314 C.E.

The third of the African popes and the 49th pope overall was St. Gelasius I. He was born in Rome of African parents and governed from 492 to 496 C.E. He is described as “famous all over the world for his learning and holiness” and “more a servant than a sovereign.” He died on Nov. 19, 496 C.E. and like St. Victor I and St. Miltiades, St. Gelasius I was canonized. As a saint, his Feast-day is held on the 21st of November.

The Severan Dynasty

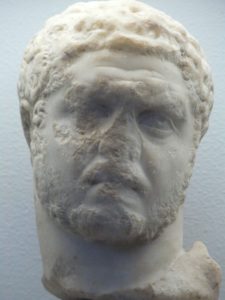

Records state that Septimius Severus was born in Leptis Magna on the North African coast (modern-day Libya) on April 11 in either 145 or 146 C.E. After the death of Emperor Marcus Aurelius and succession by his son Commodus, Septimius received his first military posting, commander of a Roman legion in Syria.

In 193 C.E., Septimius Severus became emperor of Rome. It was just four years earlier, in 189 C.E., that Victor I, an African, became pope. Four years after Septimius became emperor, in 197 C.E., Tertullian’s Apologia was published. In 203, 10 years after Septimius became emperor of Rome, the exceptionally brave St. Perpetua (an African woman) and her companions were martyred. In addition, by the end of the second century of the Christian Era more than one third of all of the members of the Roman Senate were born in Africa and Africans were dominant in Rome’s intellectual life.

This dynasty, known to historians as the Severan Dynasty, began with the accession to the throne of Septimius Severus in 193 C.E.

Septimius spent much of his reign ruling the Roman Empire on the move.

In 203 C.E., Septimius had a mighty arch constructed in the imperial forum. This monument is considered one of Italy’s most important triumphal arches. Septimius is even said to have built a marble tomb for Hannibal Barca — early Rome’s African nemesis. Indeed, because of his own African origins, Septimius has been referred to as “Hannibal’s revenge.” Septimius Severus is also said to have written an autobiography (which, unfortunately, has not survived) late in his life.

After a distinguished career characterized by administration reorganization, exploits on the battlefield, extensive travel, and an intensification of Christian persecution, Septimius, the man from Africa, died conducting yet another military campaign, this one in York in northern Britain, on Feb. 4, 211 C.E. He was 65 years of age and had been in poor health, suffering severely from gout, for years. He had enjoyed a highly distinguished reign of 17 years, eight months and three days, and he was the last Roman emperor to die of natural causes for almost 100 years.

Septimius Severus was succeeded in 211 C.E. by his two sons, Lucius Septimius Geta (211-212 C.E.) and Marcus Aurelius Antoninus aka Caracalla (211-217 C.E.).

Then came the reign of Severus Alexander (222-235 C.E.). Born Marcus Julius Gessius Alexianus in Caesarea, Phoenicia, Severus Alexander was the last representative of the Severan Dynasty. He is responsible for a triumphal arch at Dougga, Tunisia. He restored the Roman Coliseum to its ancient status, and his assassination after a 13-year reign brought the era of Severan domination at Rome to an end. In Rome, Alexander’s body was laid to rest in a specially made tomb. He was deified by the senate in 238 C.E.

This line of rulers, from Septimius Severus to Severus Alexander, 193 C.E. to 235 C.E., is known as the Severan Dynasty.

The African Presence in Rome: A Reading List

Birley, Anthony. Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. Garden City: Doubleday, 1972.

Rashidi, Runoko. Black Star: The African Presence in Early Europe. London: Books of Africa, 2011.

Raven, Susan. Rome in Africa. 3d ed. London: Routledge, 1993.

Snowden, Frank M., Jr. Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1970.

*Runoko Rashidi is a historian and lecturer based in Los Angeles and Paris. His most recent works are Black Star: The African Presence in Early Europe in 2011 and African Star of Asia: The Black Presence in the East in 2012. Runoko is currently leading tours to Europe in August 2014 and Nigeria and Cameroon in December 2014.