“Ancient China and the Far East, for example, must be a special area of African research. How do we explain such a large population of Blacks in southern China, powerful enough to form a kingdom of their own?”

While in September 1998, a scientific study posted in the Los Angeles Times concluded that:

“Most of the population of modern China — one-fifth of all the people living today — owes its genetic origins to Africa.”

From the realm of the physical anthropology of early China, according to the preeminent scholar in the field, Kwan-chih Chang:

“Skeletal remains from the Hoabinhian and Bacsoinan strata, similar to those found in southwest China, bear Oceanic Negroids features.”

The first Black people in China then — the people who are probably the first of any people in China — were apparently Black people akin to the Batwa of Central Africa and the people of the Andaman Islands today — we call the Diminutive Africoids. They survived well into the historical periods. The presence of Diminutive Africoids (whom Chinese historians called Black Dwarfs) in early southern China during the period of the Three Kingdoms (ca. 250 CE) is recorded in the book of the Official of the Liang Dynasty (502-556 CE).

They are said to be Diminutive Africoids and are variously called Pygmies, Negritos and Aeta. They are found in the Philippines, northern Malaysia, Thailand, Sumatra in Indonesia and other places.

Chinese historians called them “Black dwarfs” in the Three Kingdoms period (AD 220 to AD 280) and they were still to be found in China during the Qing dynasty (1644 to 1911). In Taiwan they were called the “little Black people” and, apart from being diminutive, they were also said to be broad-nosed and dark-skinned with curly hair.

Similar groups of Black people have been identified in Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia, and it seems almost certain that at one time a belt of Black populations of this type covered much of Asia, including early China and especially southern China.

So there is little doubt that in the early ages of China, a Black presence was prevalent. Now what of African presence in the great civilizations of China? Ivan Van Sertima always preached that “It is one thing to say that you were first and yet another to say what you did.” So what did Africans do in ancient China? What was their status? What positions do we find them in?

Regarding the African presence in early China civilization, three dynasties in particular stand out — the Shang, the Tang and the Yuan.

The Shang Dynasty (1766-1027 BCE), China’s first dynasty, dating from the 18th to the 11th century BCE, apparently had a Black background, so much so that the conquering Zhou described them as having “Black and oily skin.” Bronze vessels, such as Le Tigresse are thus an extremely important component to our case and helps buttress our position.

Le Tigresse is from the late Shang Dynasty period, about 1250 BCE. It is from Hunan Province and measures about 2 feet high. The vessel was intended to hold fermented beverages and is unquestionably the most famous and splendid object in the Cernuschi Museum. The vessel depicts a feline, a tigress with an open mouth, holding a small human in a close embrace with its front paws. For years, I had thought of the small human figure as a child. But on closer inspection, it appears that it may well be an adult. Is it a Diminutive Africoid? Whether adult or child, the features are clearly Africoid and may well be a depiction of one of the Diminutive Africoid-types associated with early China, protected in the powerful embrace of a tigress.

The entire effect is accentuated by the dark green, almost black, brilliance of the vessel, and the calm demeanor shown in the person’s face suggests an ease and confidence in its surroundings. Le Tigresse was acquired by the Cernuschi in 1920.

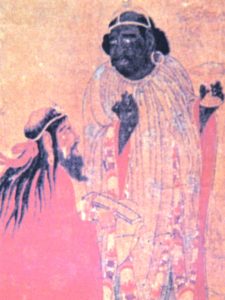

In the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) founded by Kubilai Khan, the Black presence is visible in a number of notable paintings. The first of these paintings by the Yuan court artist Liu Guandao in 1280, now in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan, is of a Mongol hunting scene. Specifically, the painting depicts two powerful looking Black men on horseback with Kubilai Khan during a hunt. Kubilai Khan was arguably the most powerful man in the world at the time and the easy posture that these men are depicted in gives one reason to think that that they are more than the Khan’s bodyguards, more than mere soldiers but quite possibly nobles or high officials of the Yuan court.

The second painting is a handscroll depicting “tribute bearers” toward the end of the Yuan Dynasty, about 1350 CE. It is housed in the Asian Art Museum, Avery Brundage Collection, San Francisco. The painting depicts four Black men, one of which is of great prominence.

What is most striking about the Shang Dynasty Yu vessels, the Tang Dynasty statues and the Yuan Dynasty paintings — all clearly Africoid — is that race and ethnicity of the people depicted are never mentioned, and if one does not see these objects for themselves you would never guess, from reviewing the relevant literature, they were Black.

Speaking of which, the famous Chinese sage, Lao-Tze (ca. 600 BCE), by tradition, was “Black in complexion.” Lao-Tze was described as “marvelous and beautiful as jasper.” Magnificent and ornate temples were erected for him, inside of which he was worshipped like a god.

Such is our brief sketch of the Black presence in early China. What I have found most interesting in my researches, including the work that I am doing on China today, is the failure, I am sure deliberate, to mention the race or ethnicity of clearly Africoid objects of art. Indeed, it seems to be even more extreme in the case of the African presence in Asia than the cover-up of the African origins of ancient Egypt. This cover-up — we must call it that — of the African presence in classical civilizations is truly a global phenomenon.

*Runoko Rashidi is a historian, writer, lecturer and researcher based in Los Angeles, California. He has written extensively on the Global African Presence and leads tours to various sites around the world. This essay is culled from his most recent work African Star over Asia: The Black Presence in the East, published by Books of Africa in 2012. His upcoming tours include the African heritage in Mexico in July 2014, the African heritage in Europe in August 2014 and Nigeria and Cameroon in December 2014. For more information write to [email protected] or go to www.travelwithrunoko.com

SOURCES:

Chang, Kwan-chih. The Archaeology of Ancient China. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963.

Chi, Li. The Formation of the Chinese People: An Anthropological Inquiry. 1928; rpt. New York: Russell and Russell, 1967.

Komaroff, Linda. Gifts of the Sultan. New Haven: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2011.

Quartly, Jules. The Taipei Times, Nov. 27, 2004.

Rogers, J.A. Sex and Race, vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Helga M. Rogers, 1968.

The Los Angeles Times, Sept. 29, 1998.

Williams, Chancellor. The Destruction of Black Civilization. Chicago: Third World Press, 1976.