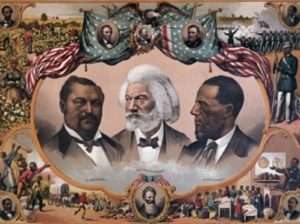

Reconstruction-era leaders Sen. Blanche K. Bruce (R-MS), Frederick Douglass and Sen. Hiram Revels (R-MS).

At the Iowa Democratic town hall sponsored by CNN on Monday night, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton came under fire for a comment she made about the Civil War and Reconstruction, with allegations that she engaged in historical revisionism. In her statement, Clinton was accused of lamenting Reconstruction:

You know, he [Abraham Lincoln] was willing to reconcile and forgive. And I don’t know what our country might have been like had he not been murdered, but I bet that it might have been a little less rancorous, a little more forgiving and tolerant, that might possibly have brought people back together more quickly.

But instead, you know, we had Reconstruction, we had the re-instigation of segregation and Jim Crow. We had people in the South feeling totally discouraged and defiant. So, I really do believe he could have very well put us on a different path.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates explained in the Atlantic, Clinton, whether knowingly or not, was expressing a racist narrative of history that was dominant until recently, reflecting a sense of national amnesia. It reflects the “The Dunning School” or “Lost Cause” moniker, the notion that Reconstruction was a bad idea forced upon the South by Northern radical lawmakers seeking revenge. This reasoning was used to justify the regime of violence perpetrated against Black people.

“The result was a savage and corrupt government which in turn left former Confederates, as Clinton puts, it ‘discouraged and defiant,’ ” Coates said.

That narrative conveniently excludes Lincoln’s assassination by a white supremacist, and Andrew Johnson, another white supremacist who assumed the presidency, as the federal government turned a blind eye to white terrorism and the exploitation of Black labor in the South.

Meanwhile, Luke Brinker at Policy.Mic notes that on her statement, Clinton conflated Reconstruction — which helped to establish rights and reforms for the benefit of emancipated enslaved people, and led to an emergence of Black political power — and Jim Crow segregation, America’s own brand of racial apartheid.

In an 1877 compromise, Republicans agreed to end Reconstruction, leading to an all-inclusive system of oppression for Black people. Brinker pointed out that critics noted similarities between the candidate’s words and “that of revisionist historians who argue that Northern radicals imprudently alienated the South by pursuing measures like black suffrage, non-discrimination codes and public education.”

This comes as Clinton hopes to solidify her lead among Black voters, and at a time when Bernie Sanders hopes to make some headway and is showing signs of gaining in a number of early primary state contests.

Hillary Clinton

Ed Kilgore in New York Magazine offered in Clinton’s defense that it is uncertain whether the “discouraged and defiant” people in the South to whom she referred were the white terrorists defending Jim Crow or their victims. However, he found her statement about Reconstruction disturbing, and an ineffective means to discuss bipartisanship, adding that “I hope she can find a way very soon to address the history of racism in the United States that shows no influence of the Dixified history in which ‘old times there are not forgotten’ but lied about.”

Further, in a commentary in the Huffington Post, Tom Donnelly — Counsel for the Constitutional Accountability Center — wrote that Clinton’s response did offer some truths, specifically that the nation would have been better off with Lincoln during Reconstruction rather than the racist Andrew Johnson.

“However, it’s not at all clear that Lincoln would have pursued a ‘generous’ and ‘patient’ path,” Donnelly wrote, speaking of a Lincoln who adapted and evolved throughout his life, and, according to historian Eric Foner, may not have issued the Emancipation Proclamation, allowed Black soldiers to serve and fight in the Union army, or supported Black suffrage had he died in 1862.

“Given this track record, would the ever-evolving, morally imaginative Lincoln have remained patient, generous, and charitable in the face of growing Southern intransigence? We will never know,” Donnelly added. “But what we do know is the actual constitutional legacy left behind by the forgotten leaders of Reconstruction — leaders like Thaddeus Stevens, John Bingham, Charles Sumner, and Frederick Douglass.”