On Wednesday, Zimbabwe signed a $3.5 billion agreement to compensate white farmers whose land was expropriated by the government and re-allocated to Black families.

Robert Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe, led a land reform program 20 years ago that forced white farmers off of their land. The compensation deal is intended to rectify Zimbabwe’s long-standing conflicts surrounding the controversial land redistribution policies. Mugabe was forced out of office during a 2017 coup d’etat.

“This momentous occasion is historic in many respects, brings both closure and a new beginning in the history of the land discourse in our country Zimbabwe,” said the country’s current president Emmerson Mnangagwa at the State House on Wednesday.

The agreement states that half of the $3.5 billion sum should be paid within 12 months of signing, and that the entire sum should be paid within the next five years.

Zimbabwe doesn’t have the money to fulfill the financial terms of the agreement, and will rely on long-term bonds and attempt to raise funds from international donors to compensate the farmers.

The agreement says the farmers will be compensated not for the lost land, but for the lost infrastructure. Compensation for the expropriation is called for in Zimbabwe’s constitution, which was adopted in 2013 when Mugabe was still in power.

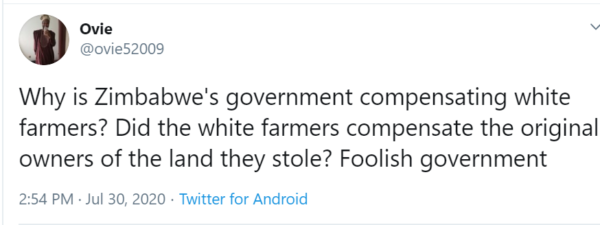

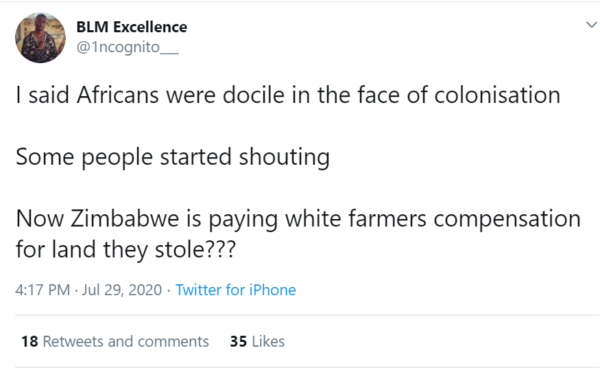

Mnangagwa hope to improve relations with the West through the multi-billion dollar deal, but the agreement has left the country divided. While Andrew Pascoe, a representative of the mostly white Commercial Farmer’s Union of Zimbabwe, applauded the deal, saying it resolved a long-standing issue, people on social media have responded critically to the agreement.

“What’s wrong with our leaders?” asked Twitter user Siya_Gw on Friday as news of the deal spread on social media.

Activist and attorney Dr. Shola Mos-Shogbamimu asked when Britain would compensate the African nations it exploited.

Two decades ago, then-president Robert Mugabe also argued that expropriating land from white farmers was justified because Zimbabwe’s best land was reserved for whites during the nation’s colonial period.

Analysts say it is unlikely that Zimbabwe will gain enough funds to pay for the deal by relying on the bond plan, citing the nation’s $8 billion debt and high inflation.