The city of New York is commemorating the state’s first free Black community after members of that community were pushed out of their neighborhood to build what is now Central Park.

Seneca Village began in 1825, when Black downtown residents started to buy property in the West 80s neighborhood, according to the Central Park Conservatory, which is installing the monument.

“Researchers believe this new community provided refuge from crowded conditions and discrimination that was prevalent in New York City,” Conservatory officials said on its website.

By 1855, Seneca Village had approximately 225 residents, made up of mostly Black homeowners and a small number of Irish and German immigrants, the Conservatory said.

Related: 10 Thriving Black Towns You Didn’t Learn About in History Class

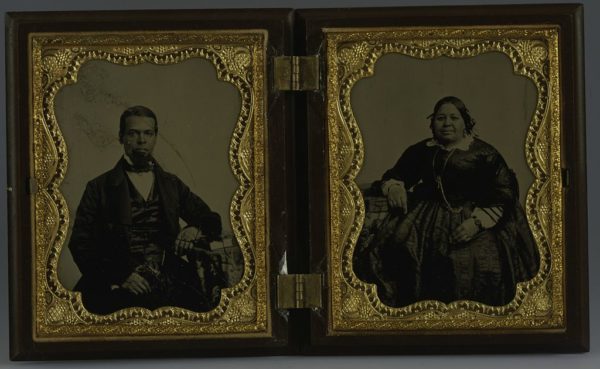

The monument will showcase pioneers Albro Lyons, Mary Lyons and their daughter Maritcha Lyons, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s office announced Tuesday in a news release.

“Along with the planned Women’s Suffrage monument, it will be the first commemorative sculpture placed within Central Park’s borders since the 1950s,” officials said in the news release.

Albro Lyons turned a family residence into a refuge for escaped slaves called a Colored Sailors Home, according to the Black Gotham Archive, a project by Carla L. Peterson.

Maritcha Lyons, a schoolteacher, built in 1892 one of the first women’s rights and racial justice organizations in the United States, the Woman’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn, according to an essay written by Val Marie Johnson in the Journal of Urban History.

Michelle Commander, associate director and curator of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s Lapidus Center, said in the city news release that the Lyons family is significant for not only making the lives of their relatives better but “for their dedication to ensuring the freedom and education of those that they helped shuttle to freedom via the Underground Railroad.”

“We often traverse towns and cities unaware of their full histories, let alone the battles that took place,” Commander said.

The monument is expected to be placed on the western side of the park near 106th Street, but the proposed location has prompted concerns online because it’s not where Seneca Village was originally located.

Raul Rothblatt, a New York activist, called the city’s proposed location “BS” in a tweet Oct. 23.

“If we want to honor the home of Albro & Mary Lyons, then build it where it was. #CentralPark oliterated Seneca Village—we have a chance 2 restore history where it happened. #BlackLandmarksMatter,” he said in the tweet.

The city said in the news release that the location was chosen to reflect “the family’s broader role in events, movements, and institutions that influenced the entire city.”

“The proposed site, which is near the recognized site of the historic Seneca Village where the Lyons owned property, also represents one of the locations along the park’s perimeter where its original designers intended for monumental artworks to be placed, as places that mark the transition from the city into the park,” city officials said in the release.

The monument will be funded by donations from the Ford Foundation, the JPB Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, the mayor’s office reported in the news release about the project.

Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, said in the release “what – and who – we memorialize publicly is a choice, and a statement about our values and the histories we, as a society, want to preserve.”

“This is not just a statue that captures the past – it’s a symbol for the future that speaks to who we are as a city and a nation,” Alexander said.