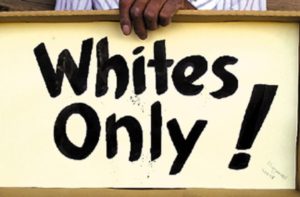

Michael Fagans Leon Grant holds one of the original “Whites Only” signs that he helped get removed from Phoenix in the 1950s.

Unfortunately, well into the second decade of the 21st century, discrimination in the housing market against African-Americans remains far from rare. Although the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has reported that the most blatant forms of housing discrimination have declined since 1977, it revealed that home seekers of color are currently told about and shown fewer homes and apartments than whites, a discriminatory practice known to “raise the costs of housing search for minorities and restrict their housing options.”

Such discriminatory practices are hard to confront, given they are commonly invisible to the client, often being enacted behind the scenes in corporate boardrooms, real estate agencies or the minds of agents. This is why some recent home buyers have been alarmed to find their deeds contain blunt, racist and exclusionary language informing them that African-Americans are not allowed to buy the homes they now own.

“No person other than one of the Caucasian race shall be permitted to occupy any portion of any lot in said plat or any building thereon except a domestic servant actually employed by a Caucasian occupant of said lot or building,” reads one such restriction in Washington state.

“What I didn’t know was that this language was still in the deed,” recounted Julie Fahey, a Democrat in the Oregon House of Representatives from Eugene. In February, Fahey, who is white, successfully sponsored a bill to facilitate the removal of offensive covenant language after encountering such a deed upon buying her house in June 2015. Though well aware of America’s long and ongoing history of racial and ethnic discrimination in housing policy, the lawmaker admitted to being “surprised” by the blunt nature of the covenant. The legislation, recently signed into law by the governor, addresses the costs and difficulties of removing such language.

“The legislation simplifies the process for getting the language taken out of the deeds of home,” explained Fahey, noting the cumbersome and costly nature of the removal process and how it requires the notification of all owners, lienholders and those with easements by “certified proof of service, which can be quite expensive.” The biggest change that we made in the law, continued Fahey, was “instead of requiring certified proof of service, you can do certified mail and sign an affidavit saying that you made a good faith effort to contact the people that have an interest in the property so it reduces both the administrative requirements and the associated costs.”

Though such racist covenants were outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the language has remained on deeds across the country ostensibly due to the legal complexities and costs involved in removing them. Along with Oregon and Washington, whites-only covenants remain on property deeds in California, Missouri, South Carolina and numerous other states. In 2009, the California Legislature passed a bill to have racist covenants purged upon the purchase of a property, only to have the legislation vetoed by then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger because of associated costs and the fact that residents can request to have the covenants removed.

While Fahey was initially taken aback by the racist language on her own deed, the ongoing existence of housing inequities in her state and beyond comes as no surprise. “It is very clear that there are disparities in the level of home ownership in Oregon and across the country by race,” stressed Fahey, reporting that recent legislative session data showed that “over 50 percent of white households in Portland own homes while it’s closer to 28 percent for black households.” Such gaps, she said, are why another recently passed bill, House Bill 4010, tracks racial disparities in homeownership in the state while establishing a task force to determine “what kind of specific policy solutions the legislature should be advocating for to try to remedy some of these disparities.”

In America, such inequities are deeply rooted. Racially restrictive covenants first came about as a response to the Great Migration of African-Americans from the South to Northern cities, and the 1917 court ruling Buchanan v. Warley, which declared municipal racial zoning unconstitutional. Since the ruling did not cover private agreements, restrictive covenants evolved as a way to perpetuate residential segregation as property owners, real estate boards and neighborhood associations conspired to only sell to white people. Such covenants proliferated upon the Corrigan v. Buckley decision of 1926, when the U.S. Supreme Court decision validated their usage.

In 1933, during the Great Depression, the federal government sought to remedy a national housing shortage through its Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a New Deal institution that increased both accessible housing and its accompanying segregation. Suburban communities were mass-produced for middle-class and lower-middle-class white families while African-Americans were herded into urban housing projects. The establishment of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934 further exacerbated this segregation by enabling redlining, or the refusal to insure mortgages in or about African-American communities. Simultaneously, the FHA — contending without evidence or merit that integrated housing would decrease the property values of whites — subsidized suburban developments across the country that required that none of the homes be sold to Black buyers.

“It was the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, not a private trade association, that pioneered the practice of redlining, selectively granting loans and insisting that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant,” wrote Ta-Nehisi Coates, in his classic June 2014 article on reparations in The Atlantic. “Millions of dollars flowed from tax coffers into segregated white neighborhoods.”

“The restrictive covenant became so fashionable that in 1937 a leading magazine of nationwide circulation awarded 10 communities a ‘shield of honor’ for an umbrella of restrictions against ‘the wrong kind of people,” revealed the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in February 1973. “By 1940, according to a magazine article, 80 percent of both Chicago and Los Angeles carried restrictive covenants barring black families.”

Given middle-class families, particularly in the 20th century, groomed their wealth from the equity in their homes, the impact of such federally-subsidized discrimination is well represented by the ongoing disparities of today. African-American incomes on average, recently reported NPR, are “about 60 percent of average white incomes. But African-American wealth is about 5 percent of white wealth.… So this enormous difference between a 60 percent income ratio and a 5 percent wealth ratio is almost entirely attributable to federal housing policy implemented through the 20th century.”

“Part of why I brought this bill forward was so that it could be a teachable moment,” offered Fahey, noting “I really wanted to further the process of educating the public and the legislature about our history of discrimination in housing policy in Oregon and also around the country.” Consistent with her intentions, Fahey actually read the racist covenant language on the floor of the Oregon House. “That was part of what the goal of the bill was, to make sure that people understood our history so that when this task force comes back with policy recommendations for change, people are aware of it and potentially more willing to listen to and support those recommendations.”

For Fahey, the end goal more than justifies the means.

“I know that this legislation, in and of itself, does not do anything to remedy the fact that we discriminated against people of color for decades in this country from a housing perspective, and that discrimination still reverberates today,” acknowledged Fahey. “But I am hopeful it helps to lay the groundwork for actually making some policy changes that will fix it.”