There has been a mound of research on the effects of slavery on the African-American psyche. However, little research has been conducted about the effects of slavery on the white mind and how it negatively impacted their cultural identity. Most European-Americans did not receive a direct financial benefit from the institution but they have benefitted indirectly and were psychologically impacted by the institution. The current financial and social landscape that exists in America is directly linked to the institution of chattel slavery.

HISTORICAL IMPLICATIONS

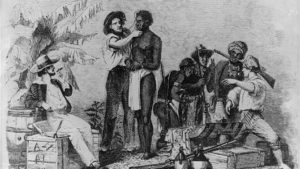

The justification of the enslavement of African people was based on an economic need. As a result, a false narrative of African inferiority was created and perpetuated through the idea of white superiority. Those that didn’t own slaves developed a false sense of superiority and real experience with privilege. The belief in this narrative, even for poor whites, set the groundwork for arrogance and misguided power that were propped up by laws. When explaining slave code laws, UShistory.org notes, “Legally considered property, slaves were not allowed to own property of their own. They were not allowed to assemble without the presence of a white person. Slaves that lived off the plantation were subject to special curfews.”

These were just a few laws that represented the hundreds on the books that reinforced the psychological narrative of white superiority by subjecting African people to unjust laws that maintained inferiority. In short, this false inferiority narrative began to be reinforced not only by plantation owners, but through the quasi caste system created through governmental, financial and social policies. This institution helped to lay the groundwork for the economic and social landscape that currently exists.

Not only did European-Americans benefit from this false psychological narrative but they also benefited indirectly from the financial implications and benefits. Cheap, and often times, free land helped create an upper hand for whites to begin to justify their false sense of superiority.

Beginning as early as the 16th century, many European immigrants were given land grants to spur settlement. Land, more than any other natural resource in America was the foundation for wealth in the United States. So, as white America was developing with their dependence on slave labor, Blacks were reduced to enslavement and, or servitude for hundreds of years. Instead of whites fully understanding this narrative, they were forced to believe that they somehow, totally, “pulled themselves up by their boot straps” to create a democratic and fair free market system.

Professor of American history, James Horton explains, “We need to do some studying about the psychological impact of slavery on slave holders. We know that it had a devastating impact on slaves. We know how slaves suffered under this institution. But I would argue that whites did it to themselves too, and that we need to understand. If we’re ever going to get together as people, to understand ourselves in this society, we need to understand what this institution of slavery has meant for the shaping of American culture generally, for the shaping of the society in which we live today. And I would argue, it has been tremendously influential.”

Without a true understanding, Americans begin to exist in a society that is, to some degree, make believe. In this fairytale, Whites are the natural leaders and Blacks and all other non-whites become second class citizens. White anti-racist essayist, Tim Wise, disagrees with this make believe version of history. He asserts, “We are here because of blood, and mostly that of others; here because of our insatiable and rapacious desire to take by force the land and labor of those others.” The national and global economic benefit blinded many American citizens from their human consciousness.

Because social reform takes generations, this same consciousness still exists within many white minds today. It can be easily seen in the popular media response to the protests in Baltimore. In speaking of Baltimore’s response to unfair treatment, Wise notes, “It is bad enough that much of white America sees fit to lecture Black people about the proper response to police brutality, economic devastation and perpetual marginality, having ourselves rarely been the targets of any of these.”

This notion of a “proper response” is directly linked to the slave codes of the 17th century that attempted to control Blacks in an effort to maintain the narrative of superiority. Without taking a critical look into how the conditions of this country developed, it will be difficult to find a solution to the current and continued social unrest.

This is why media outlets view Black social unrest as “thuggish” while white social unrest is considered legitimate protest, i.e. The American Revolution. This media labeling supports the inferiority narrative. Instead of taking an in-depth look at the complexities of urban life and the foundations of this country, often the behaviors of a few are compounded and broadcasted to support the superiority narrative.

Disproportionate wealth, urban poverty, historical amnesia and judgment over empathy are all effects of the institution of slavery on whites. If this country is to ever begin the healing process, it is extremely important for white America to take a look at the history that created the system in which we all exist.

For hundreds of years, European-Americans have only had to look through the window of prejudice instead of the mirror of reflection. American history has been one of superior white washing rather than examining a holistic viewpoint of society. This helps to create a false sense of self that reinforces false projections to people who are non-white.

America begins to heal when all Americans start to critically examine the historical implications that have created the conditions in which we all live.