Almost monthly, Black men are let out of America’s prisons after having chunks of their lives stolen away for crimes they did not commit. Wrongful convictions are a tragedy to which only those who have experienced it can relate and accurately express the range emotions that tear away at you.

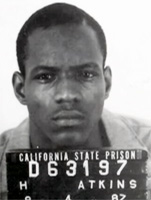

Herman Atkins spent 12 years in some of California’s most notorious prisons for a rape he did not commit. He was exonerated in 2000 when DNA evidence proved what he had said all along. He spends his days now in law school in San Diego, working to become an attorney to represent the disenfranchised who are arrested under questionable circumstances.

Atkins tells his emotional and heart-wrenching story in a three-part series to Atlanta Blackstar.

Part I: A Ball of Confusion, by Herman Atkins

(as told to Curtis Bunn)

I stood in the courtroom as a young man of so much promise, lofty ambition and, especially, hope. But in an instant, I felt lifeless, as if the blood in my body drained onto a steel autopsy table.

In one word—“guilty”—I was stripped of any pride I had, any dignity, any dreams. All that was left was anger . . . and disbelief.

I did not rape that woman, would not rape any woman, could not even conceive of forcing myself on someone. And yet the jury said I had, although I had never been to or even heard of Lake Elsinore, California, where the alleged crime took place, and had never seen the “victim,” who testified that I was her assailant.

Only someone who has been falsely accused and convicted of something he did not do can understand the emotions that come with such a plight. The fear. The loss. The anguish. The disbelief. The hopelessness.

At twenty-one, my life that had potential turned into the kind of mess no one even considers. A forty-five-year prison sentence was handed down to me for a crime that I did not commit, even though the prosecutor told the jury that the forensic evidence did not prove I was there.

My mind shut down. All this time later, no matter how hard I try, I hardly remember leaving the courtroom. It was as if everything went dark.

I ended up alone in an eight-man cell with my heart overcome with hate: for the judicial system, for white people, for any symbol of authority. A corrections officer saw the pain in my eyes and took me to a padded cell, where they bring an inmate they feel might hurt himself. He gave me a roll of toilet tissue and shut the door.

For the next two hours, I cried. I cried until my eyes burned and my head hurt. It was a breakdown I had never experienced, one that showed me that you only have so much control over your emotions, so much control over your life.

Everything I was taught and raised on—the philosophy and beliefs of my parents about how great the American justice system was—was destroyed. My life was crushed because someone told a lie on me. In that simple act, I was reduced to nothing.

They took a sledgehammer and tore up any hope I had for myself. Most people have no idea how devastating it is to believe that your life is over, just as it should be starting.

I went below a low point. I didn’t know what to do to myself, with myself and I didn’t know what was about to come at me.

I was scared to death.

A dozen years later, on February 18, 2000, I was released from prison after DNA evidence proved what I insisted all along: that I did not commit rape on April 8, 1986. Between the conviction and the release twelve years later, I experienced a personal hell amid a slew of penitentiaries full of violent criminals, experiences made more tragic by my innocence.

To get to where I can write about it now has been an odyssey that I believe would have broken a lesser person.

The conviction by itself could have killed me. Watching a man stabbed to death mere feet away could have killed me. The mental anguish of waking up everyday for twelve years to no prospects of a better life could have killed me.

Sixteen months in “the hole”—where I spent twenty-three hours a day in a small, dingy cell—could have killed me. Not seeing my mother for all my time in prison could have killed me. Watching myself turn into something ugly and bitter and perpetually angry could have killed me. The three inmates who attacked me on three separate occasions could have killed me. And yet, through the mighty grace of God, I survived.

But it was not easy.

Because I protested not receiving food one night and inadvertently broke a window, I was assigned S.H.U. detail. You might have heard Denzel Washington refer to it in his Oscar-winning role as a dirty cop in the film Training Day. It’s pronounced by the initials, “shoe,” but written S.H.U. detail, as in Special Housing Unit. In most instances in the world, the word “special” means something good. Not in this case.

In “S.H.U detail,” you are housed in a cage for all but sixty minutes a day. You get thirty minutes to shower and thirty minutes to walk in the yard. That was it. That was my daily routine.

The horror was made slightly less awful by the conversations I would have through the air vents with a neighboring “S.H.U.” resident named Michael Stokes.

He already had been in the hole for eight years and there was no telling when he would get out. He and I used to talk through a vent that led from my cell to his. But my attitude was so nasty and angry that he stopped talking to me.

I asked him why, and he said something to me that started to change my life: “You’re so bitter and hostile that you’re not hearing me. Look, man, first of all, you’re young. And if what you’re telling me is true, you don’t need to be back here with me. You need to be in the ‘main line’ (the regular prison) in somebody’s law books trying to figure out how the hell those people did what they did to you and got away with it.”

And even in my bitterness, that made a lot of sense. He started calming me down. I was only four months into the sixteen months in had there. I asked him what I should do and he gave me a book, The Mis-education Of The Negro by Carter G. Woodson.

“And when you finish reading it,” he said, “then let’s talk.”

I read it and that book had a profound effect on me. During my incarceration I read more than two hundred books. But Mr. Woodson’s book was the first, and it touched on a philosophy that whites had about Blacks, which was “If you want to hide something from a Ni***, put it in a book, because in a book a Ni*** won’t look.”

When I read that, I was like, “What? This is not true. White folks actually think about this? This is what their thought process is?”

That alone woke my mind up. When I finished the book, Michael Stokes and I started talking again, and I could see things more clearly. My thought processes immediately changed. But it changed for Black empowerment, for self-empowerment.

I wanted to learn about my history. I had the history of my past, before my ancestors were brought here; the history of an African born and raised in America; and then I had my individual history from the time I was born.

I studied those histories and religion, economics. . . anything I could, and I absorbed it. And it also sent me to law books. When I got back to the “main line” I was armed with a different attitude to do something about the injustice done to me, even if I never believed anything would come of it.

And don’t get me wrong; I was still bitter and angry. The difference was I was now determined. I was not going to accept what was handed to me. Even if it did not get me the results I wanted, I was not going to just take it. So, I pored through books on rape cases and misidentifications.

One day, this inmate said to me: “You have your head in those law books too much for someone so young.”

Now, rapists and child molesters are treated like the lowest of the low in prison. So I did everything I could to shield why I was in there. But something in my spirit with this guy allowed me to open up to him. I was reluctant. But I told him what my charges were.

He said, “Hmm. So what are the issues that you’re trying to raise?”

I told him about all the research I had done, the cases I had read about rape and misidentification. He said, “It seems to me that you’re trying to chop down a tree and now you’re down to the stump and it’s hard to pull it up. Well, there is a legal defense team by the name of the Innocence Project and they deal with DNA testing.”

I didn’t know anything about DNA testing at the time, but he educated me on it. He said that if I wrote them a letter, he was almost sure they would take my case and “you’ll be out in a matter of months,” he said.

With all that had happened to me, I did not get excited. But knowing there could be someone out there working on my behalf did spark a little hope. So I took the information on the Innocence Project and wrote a thirteen-page letter. I knew it was too long, so I condensed it to a page-and-a-half.

It was the most important letter I ever sent from prison. It would take another six years before it all would come to fruition, but through the Innocence Project, I eventually walked out of prison and into a world that had passed me by—but one I was eager to take on.

Tomorrow: Part II, The Insanity of Hope