He was probably lactose intolerant and had more difficulty digesting starchy foods than the farmers who transformed diets and lifestyles when they took up tools in the first agricultural revolution.

The invention of farming brought humans and animals into much closer contact, and humans likely evolved more robust immune systems to fend off infections that the animals passed on. But scientists may have overestimated the impact farming had in shaping the human immune system, because tests on the hunter-gatherer’s DNA found that he already carried mutations that boost the immune system to tackle various nasty bugs. Some live on in modern Europeans today.

“Before we started this work, I had some ideas of what we were going to find,” said Carles Lalueza-Fox, who led the study at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona. “Most of those ideas turned out to be completely wrong.”

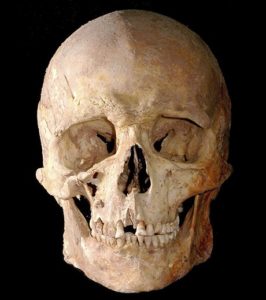

The Spanish team started their work after a group of cavers stumbled upon two skeletons in a deep and complex cave system high up in the Cantabrian Mountains of northwest Spain in 2006. The human remains, which belonged to two men in their early 30s, had been extremely well preserved by the cool environment of the cave.

Carbon dating put the remains at around 7,000 years old, before farming had swept into Europe from the Middle East. The timing fitted with ancient artifacts found at the site, including perforated reindeer teeth that were strung and hung from the men’s clothing.

The scientists focused their efforts on the better preserved of the two skeletons. After several failed attempts, they managed to reconstruct the man’s entire genome from DNA found in the root of a third molar. It is the first time researchers have obtained the complete genome of a modern European who lived before the Neolithic revolution.

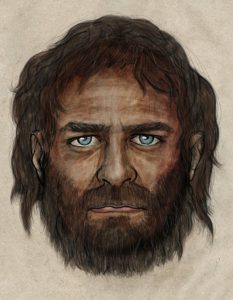

The DNA threw up a series of surprises. When Lalueza-Fox looked at the genome, he found that rather than having light skin, the man had gene variants that tend to produce much darker skin. “This guy had to be darker than any modern European, but we don’t know how dark,” the scientist said.

Another surprise finding was that the man had blue eyes. That was unexpected, said Lalueza-Fox, because the mutation for blue eyes was thought to have arisen more recently than the mutations that cause lighter skin color. The results suggest that blue eye color came first in Europe, with the transition to lighter skin ongoing through Mesolithic times.

The Spanish team went on to compare the genome of the hunter-gatherer to those of modern Europeans from different regions to see how they might be related. They found that the ancient DNA most closely matched the genetic makeup of people living in northern Europe, in particular Sweden and Finland.

The discovery of mutations that bolstered the immune system against bacteria and viruses suggests that the shift to a farming culture in Neolithic times did not drive all of the changes in immunity genes that Europeans carry today. At least some of those genetic changes have a history that stretches further back. “One thing we don’t know is what sort of pathogens were affecting these people,” said Lalueza-Fox.

Martin Jones, professor of archaeological science at Cambridge University, said the immunity genes were the most striking result. “There is a no doubt oversimplified grand narrative that the move from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled farming was initially bad for our health. A number of factors contributed, particularly living closely together with other humans and animals, shrinking the food web, and crowding-out water supplies. The authors are drawing attention to the role of pathogens in pre-agricultural lives, and that is interesting.”

Source: theguardian.com