The U.S. Supreme Court today disappointed opponents of affirmative action looking for a resounding rejection of the controversial policy as it issued a 7-1 ruling sending the University of Texas affirmative action case back to the lower court. With the ruling the court concluded that the lower court did not bring enough scrutiny to UT’s use of race.

In claiming that the lower court misinterpreted an earlier Supreme Court decision, the court has made it more difficult for University of Texas to prove that its affirmative action program is constitutional.

It is a narrow victory for Abigail Fisher, the white woman who initiated the challenge by claiming UT-Austin unconstitutionally discriminated against her after the university rejected her 2008 application under its race-conscious admissions program.

While Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, appeared to endorse the Supreme Court’s earlier decisions establishing that affirmative action is constitutional if it is used to foster a diverse student body, the court established that a race-conscious program could only be used if it was the only way to increase diversity.

The court majority felt that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit hadn’t pushed UT enough to prove that its race-conscious admissions program was the only available way to foster diversity.

“The university must prove that the means chosen by the university to attain diversity are narrowly tailored to that goal. On this point, the university receives no deference,” Kennedy wrote. “Strict scrutiny must not be strict in theory but feeble in fact.”

This “strict scrutiny” was a standard first established by the court in 1978. In the landmark 2003 decision in Grutter v. Bollinger, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor sided with the court’s four liberals to uphold the University of Michigan Law School’s affirmative action policy—though Kennedy dissented by claiming the University of Michigan did not meet the strict scrutiny standard.

In order for an affirmative action policy to meet this standard, as stressed today by the court, it must be absolutely necessary to achieve diversity on campus.

But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the only justice dissenting from Monday’s decision, felt the lower court had faithfully applied the standard set out in Grutter. “I would not return this case for a second look,” she wrote, because “the university reached the reasonable, good-faith judgment that supposedly race-neutral initiatives were insufficient to achieve, in appropriate measure, the educational benefits of student body diversity.”

After the 5th Circuit effectively banned affirmative action in Texas in 1997, UT-Austin instituted a race-neutral policy to automatically admit all applicants who placed in the top 10 percent of their high school classes. But after the Supreme Court’s 2003 Grutter decision effectively overruled the 5th Circuit decision, UT-Austin began to fill up the remainder of its entering classes with a race-conscious review of those applicants who did not quality for admission under the top-10 percent plan. That is the program that was challenged by the rejected applicant Fisher.

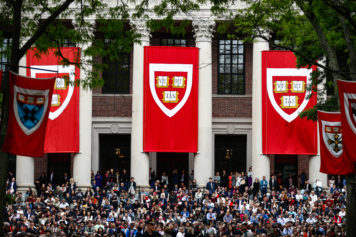

It is the first higher education affirmative-action case that has come before Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito and Sonia Sotomayor — Justice Elena Kagan, the former dean of Harvard Law School, recused herself because of her involvement with the case while she served as President Barack Obama’s solicitor general.

Justice Thomas once again voiced his strong opposition to affirmative action—although strangely he has admitted that he benefitted from it during his academic career.

“[A] state’s use of race in higher education admissions decisions is categorically prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause,” Thomas wrote. “The university’s professed good intentions cannot excuse its outright racial discrimination any more than such intentions justified the now-denounced arguments of slaveholders and segregationists.”