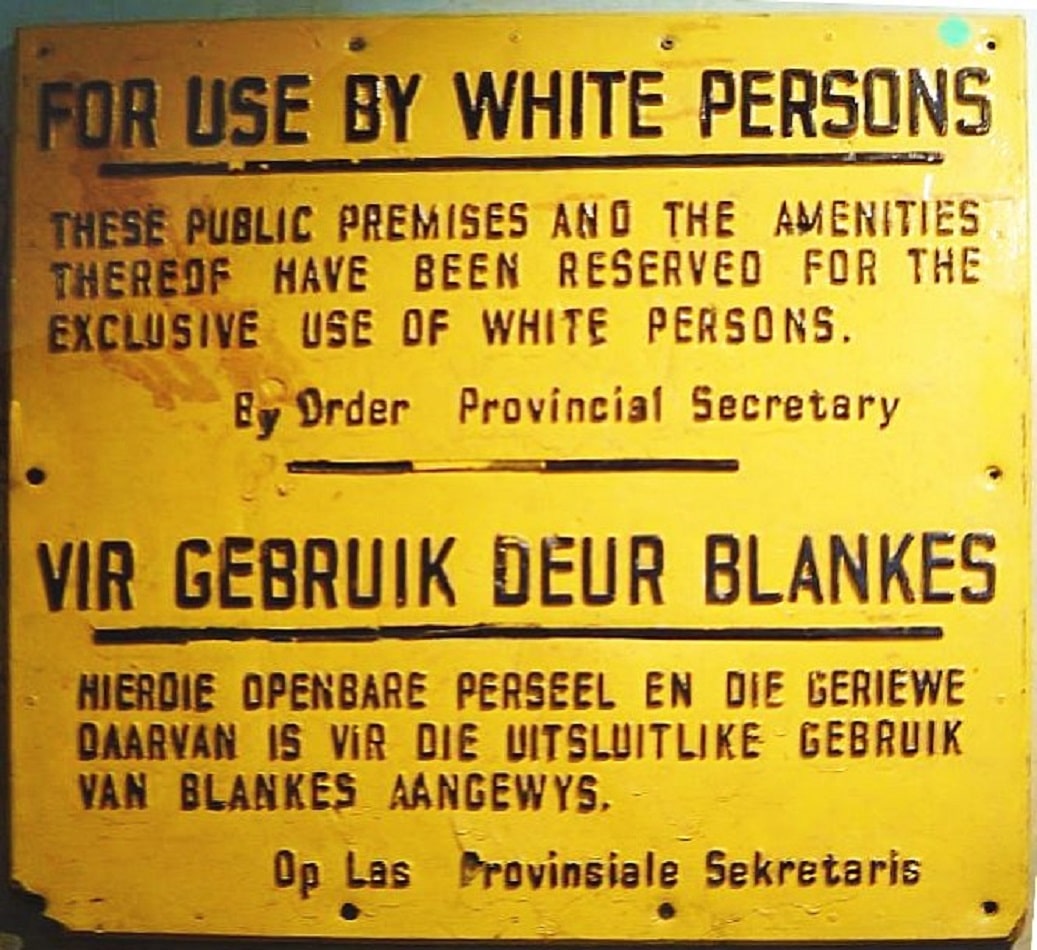

Far-right white nationalists in South Africa have promoted the debunked concept of “white genocide,” that white farmers are murdered by Blacks in an effort to exterminate white South Africans. The conspiracy theory is part of a greater reality in this country plagued by economic inequality 24 years after apartheid. Whites still own a vast majority of the land, which contributes to Black poverty. Black South Africans have made efforts to reclaim the land through expropriation without compensation. (Photo: Wikipedia)

In South Africa, a nation that is short of two-and-a-half decades from apartheid, inequality persists and land ownership remains disproportionately the province of whites in this predominantly Black African nation. This as Black South Africans have expressed frustration over the slow pace of land reform by the ruling African National Congress. Amid this backdrop, conservative white South Africans have decided to perpetuate the narrative that there is a genocide being waged against white Afrikaners, a claim which is contradicted by the facts.

In a nation that receives media attention for its levels of violence, the murder of white farmers has drawn scrutiny. Wealthy and isolated, white farmers have been targets of violent crime which white groups argue is due to racial vengeance by Black people, as Quartz reported. The Afrikaner group AfriForum, a self-described white civil rights group, has flown the South African apartheid flag and engaged in protests claiming they are persecuted and the ANC is ignoring the plight of white farmers.

However, a report from the South African Agricultural Industry finds that the number of violent farm attacks has dropped by half from a peak in 2001 and 2002. AfriForum — which has spoken with lawmakers in Washington and appeared with cable host Tucker Carlson on Fox News in the United States — disputes the report using its own, questionable data.

The conspiracy theory of white genocide has gained traction with the far right, who point to the occasional crime against a white farmer as proof of a systematic effort to kill white people. As The Outline noted, white nationalists have promoted the concept of imminent white genocide for a long time, and AfriForum is actually a far-right white nationalist group that has called apartheid “a so-called historical injustice.” Another group, the Suidlanders, has reached out to alt-right groups and media in the U.S., the UK and Australia. The Suidlanders believe in the inevitability of a race war and regard themselves as “an emergency plan initiative” to prepare South Africa’s Protestant Christian minority for violent revolution. With the argument that white people are on the verge of falling off the cliff has come Afrikaners seeking asylum in countries such as Canada, Ireland and Australia, with many of the petitions rejected, and a few granted. Australian Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton was considering fast-tracking visas for white South African farmers, who he said “deserve special attention” due to violence and land seizures, and were fleeing “horrific circumstances” for a “civilised country.”

As Channel 4 reported, the reality is that while right-wing pundits have promoted the concept that a white genocide is under way in South Africa, the argument that white farmers are at a high risk for murder simply is not true, as poor Black South Africans face a far greater risk of being murdered. According to police data, of the 19,106 murders in South Africa from 2016 and 2017, 74 were committed on farms.

As South African writer and student activist Thabi Myeni has noted, the white genocide myth has been debunked, yet it is receiving attention because of the “help of racist pundits from ultra white imperialist countries and Fox News.”

South Africa remains deeply unequal, with indigenous Black people owning less than 4 percent of agricultural land, and whites controlling as much as 73.3 percent. More important, Myeni says that the white beneficiaries of colonization, who live in gated communities and are safe and secure, are lying because Black people — who were dispossessed of their land and now live in townships packed like sardines, are struggling to take back their land.

“Grassroots movements like the Black First Land First (BLF) that are lobbying for indigenous people to take back what is rightfully theirs, have inspired mass resistance against white hegemony. Calls for reparations are mounting, black people are organizing themselves to pursue justice and making serious strides towards their liberation,” Myeni said. “Crime is rampant in South Africa, which should shock no one because our Constitution (the cornerstone of our so-called democracy) itself doesn’t seek to correct the most violent crimes this country has ever seen — white capitalism and dispossession. Where the black majority has been disenfranchised and economically excluded.”

The ANC promised 22 years ago to return land owned by white farmers back to Black people, and nearly 20,000 Black claimants have waited since that time, with critics concluding the government lacks the political will to make it happen. These claimants are labor tenants who have lived on the land for generations and farm the land in exchange for their labor and seek title to the land. The prevailing land reform policy has been based on a willing-seller, willing buyer concept, in which both buyer and seller must consent to the land purchase, and the seller, almost always white, could decide what land to sell.

The history of the politics of land ownership in South Africa goes back to the Natives Land Act of 1913, which prohibited Black people from buying or renting land in “white South Africa,” resulting in the forced relocation of Black people. Black South Africans, who are 80 percent of the population, had been relegated to homelands which comprise 13 percent of the land and are governed by traditional leaders. After apartheid, in 1994 the ANC-led government said it would return 30 percent of the land to its original owners by 2014. However, only 10 percent of commercial farmland has been redistributed, according to the BBC, with land-reform farms failing as a result of a lack of capital and skill transference, and land reform faltering due to poor government management, corruption and lack of will, few resources or support for new farmers, and resistance from white farmers. In addition, traditional leaders who control much of the rural land have stalled reform, and have undermined the rights of those living on communal lands — 15 percent of South Africa — by entering into deals with mining companies. Some critics and analysts argue that South Africa, the continent’s largest corn producer and second-largest citrus producer, should not follow the example of Zimbabwe, where the seizure of white farms resulted in economic collapse because new farmers lacked experience and capital. Others are concerned expropriation of land from white farmers would jeopardize food security and growth, and the main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, believes expropriations will hurt poor people and foreign investment.

Political groups such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a small party which advocates for the radical nationalization of all land in the country, has called on Black South Africans to occupy the land themselves. New ANC leader and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa is feeling pressure from EFF and promises to accelerate the process of land reform, considering legislation to permit land expropriation without compensation. The ruling party set out to test whether the expropriation of land is possible without a change in the constitution as the party pledged these changes to bring about land reallocation. The EFF brought a motion for land expropriation in March, which was adopted in parliament. With parliamentary elections next year, the movement of the ANC in the direction of land expropriation may serve to neutralize the threat of the EFF and their attractive message.

Ramaphosa argues that the expropriation of land without compensation will have a positive economic impact. “This [land redistribution] we should do through using a number of mechanisms. One of those is to expropriate without compensation to unlock the wealth of this land, which has been held in few hands from the days of colonialism. That alone should be able to add an injection to the growth of our country,” he said.

The World Bank has declared that land reform in South Africa is a priority, noting in a report that among the five constraints in tackling poverty and inequality in South Africa is a “skewed distribution of land and productive assets and weak property rights.” Land reform is therefore crucial in reducing poverty. In 2015, half of all South Africans were classified as poor, with poverty increasing from a low of 53.2 percent in 2011 to 55.5 percent in 2015, meaning that over 30 million out of 55 million South Africans lived in poverty.

Further, the discussion of land reform in South Africa has opened the door for a redistribution of urban land, where most South Africans live. The government owns 10 percent of the land in the country, including not just rural land but urban as well. Expropriation of urban land — whether public or private — could focus on poor families in occupied buildings and parcels, and unused state land. Urban land reform could transform the lives of Black South Africans who live in substandard, overcrowded housing as a remnant of apartheid. In a country which operates based on registered title to the land, where no deed exists, South Africa must look beyond the traditional property system to empower the dispossessed through land ownership. The South African government has decided it wants to undertake land reform. Whether real reform is delivered depends on the will and the creativity of the national leadership and the capacity of the government to follow through.