In a cruel and unusual legal twist, it is this charge of racial bias in IQ testing that is now being used by a growing number of American prosecutors to ensure more African-American and Latinx capital inmates are put to death REUTERS/Carlo Allegri

IQ tests have long been plagued by claims of cultural and racial bias. Critics from a wide range of arenas, including academia, psychology, psychiatry and activism have characterized these controversial assessments as ineffective, inappropriate and skewed toward a normative white standard. Still, the tests have endured in many fields, including criminal justice, where they act as a criterion for determining if a person convicted of a capital offense is intellectually competent enough to receive the death penalty given these assessments are commonly acknowledged to offer value in establishing a basic competency. In Atkins v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court codified this upon ruling that executing the intellectually disabled violated the Eighth Amendment and qualified as cruel and unusual punishment.

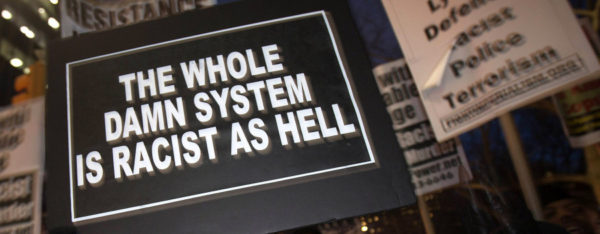

However, in a cruel and unusual legal twist, it is this charge of racial bias in IQ testing that is now being used by a growing number of American prosecutors to ensure more African-American and Latinx capital inmates are put to death.

Referred to as “ethnic adjustments,” this practice automatically boosts IQ scores, often by 5 to 15 points, for African-American and Latinx inmates convicted of capital crimes. To win a death sentence against an accused, prosecutors in at least eight states — Alabama, California, Florida, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Texas — have increasingly resorted to the summoning of expert witnesses who testify to the racial biases of IQ testing. Though these health experts commonly have no interaction with the defendants at any point, they generally argue that such racial bias accounts for the sub-competent performance on previous IQ tests for African-American and Latinx defendants and, therefore, their scores would have likely been higher if not for the bias. Such ethnic adjustments enable the capital sentencing of those who’d otherwise be deemed intellectually unfit.

“In my opinion, ethnic adjustments are outrageous,” said Robert M. Sanger, a prominent trial lawyer and professor of law and forensic science at Santa Barbara College of Law in California. His 2015 article in the American University Law Review was largely responsible for drawing attention to the prosecutorial use of ethnic adjustments. “What these so-called experts do is say that, because people of color are not as likely to score as well on IQ tests, you should, therefore, increase their IQ scores from 5 to 15 points to make up for some unknown or undescribed problem in the test,” explained Sanger, noting there is no scientific, “legal or intellectual basis for this.”

Scientific or not, Sanger has documented numerous cases where such adjustments were employed including Hodges v. State, where the Florida Supreme Court ruled that the legal significance of an African-American defendant’s low IQ score could be discounted after a prosecution expert testified, “IQ tests tend to underestimate particularly the intelligence of African-Americans.” While this claim, in itself, may certainly have merit, Sanger is more concerned with its selective legal interpretation and application.

He cited a number of cases where the Supreme Court consistently rejected the adjusting of test scores on the basis of race, the most prominent being Washington v. Davis, where District of Columbia police officer candidates claimed a skills test was racially discriminatory, as African-Americans were four times less likely to pass than white candidates. The high court ultimately concluded that, despite a Fifth Amendment equal protection component “prohibiting the government from invidious discrimination, it does not follow that a law or other official act is unconstitutional solely because it has a racially disproportionate impact regardless of whether it reflects a racially discriminatory purpose.”

The African-American candidates, recounted Sanger, felt “their scores should be adjusted upward so they could get a job, but the Supreme Court said, ‘No, we can’t do that.’ So it’s sort of outrageous that you can adjust scores upward so you can be killed, but not so you can get a job.”

In America, the racially discriminatory impact of capital punishment policy has been an ongoing source of outrage as well. The nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center reported that despite constituting only 13 percent of the population, in 2016 41.8 percent of the 2905 prisoners on death row in the United States — and more than a third of those executed since 1977 — were Black.

In Georgia, American Bar Association (ABA) data revealed that among all homicides with known suspects, those suspected of killing whites are almost five times as likely to be sentenced to death as those suspected of killing African-Americans. Similarly, in Alabama, over 82 percent of those executed since 1976 were convicted of killing white people even though more than 65 percent of all murders each year in Alabama involve Black victims. And 80 percent of the state’s current death row population was convicted of murdering white people.

“The race-conscious use of the death penalty in Alabama has always been a widespread problem,” said Angie Setzer, senior attorney with the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery-based nonprofit providing legal representation to individuals and communities impacted by poverty and unequal treatment. Setzer detailed ongoing racial disparities and inequitable practices in the state’s administration of criminal justice. “We see this playing out in the way people are charged and convicted, and we see this in the process of discriminatory jury selection,” she acknowledged. “So it’s occurring at all of these different levels in the context of a criminal case,” stressed Setzer, noting the Alabama court system’s tolerance and use of “racially biased experts is a clear example of this larger problem.”

It is a problem compounded by the wide variety of disabilities across a range of categories including, but not limited to, physical, intellectual and mental, that capital inmates commonly suffer from. While no comprehensive accounting has been attempted, the Fair Punishment Project (FPP) did reveal that at least 40 percent of the death row inmates in the 16 American counties with the most executions suffered from intellectual disabilities, severe mental illness or brain damage.

Additionally, two-thirds of those on death row in the state of Oregon exhibited “signs of serious mental illness or intellectual impairment, endured devastatingly severe childhood trauma, or were not old enough to legally purchase alcohol at the time the offense occurred.” FPP further noted the “U.S. Supreme Court has held that regardless of the severity of the crime, imposition of the death penalty upon a juvenile or an intellectually disabled person, both classes of individuals who suffer from impaired mental and emotional capacity relative to typically developed adults, would be so disproportionate as to violate his or her ‘inherent dignity as a human being.’”

Consistently, the 2002 Atkins ruling and its interpretive evolution a dozen years later in Hall v. Florida produced a more structured and clinical framework for both defining and determining intellectual disabilities in capital cases. This framework held that those with “significantly subaverage intellectual functioning” — generally yet not strictly recognized as an IQ of 70 or below — were ineligible for the death penalty provided they met two additional criteria, these being compelling “deficits in adaptive functioning” and the “onset of these deficits during the development period.” In other words, a low IQ could combine with certain inabilities to socially function and reason within one’s environment, particularly those stemming from an earlier developmental stage like childhood, to prohibit a defendant’s eligibility for the death penalty.

But with ethnic adjustments, prosecutors are finding a way to artificially inflate these IQ scores in order to execute more African-American and Latinx capital inmates. Such controversial tactics are a particularly pressing concern for Sanger, who commonly represents African-American capital defendants with serious intellectual disabilities stemming from traumatic childhoods.

“We’re not taking the worst of the worst, which is what the death penalty is supposed to be all about, which is to get the people who committed the worst crimes with intentionality and evil,” said Sanger. “Instead, we’re getting the people who are marginalized in society, and, ironically, they are often the same people who are subject to these same deprivations that would, in fact, cause them to have deficits in their IQ scores and adaptive behavior.

“If you look at the demographics of our death row inmates, you’re taking a segment of society from a lower economic strata that disproportionately suffers from mental health issues and has an IQ that is close to the limit or below the limit,” continued Sanger, noting that “maybe those 5 or 10 points that pushed them down there [below the score of 70] might have been a result of their exposure to these environmental issues.

“But you don’t add them back in.”