With opioid-related deaths on the rise, members of the White House’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction have asked President Donald Trump to “declare a national emergency.”

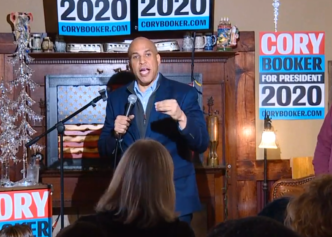

However, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker (D) has a plan that could help prevent more deaths from opioid addiction — and it comes in the form of pot legalization in all 50 states.

On Tuesday, Aug. 1, Booker introduced a far-reaching bill that would end the federal ban on marijuana and even encourage states to legalize the popular drug, NBC News reported. For him, decriminalizing marijuana would not only help begin to undo the devastating effects of the war on drugs on nonwhite communities but could also aid in curbing the deadly opioid crisis.

“I have seen a lot of very compelling preliminary data that shows there is a drop in opioid overdoses in areas that have better access to marijuana,” Booker told the network during an interview, adding that he looked forward to seeing more research that could help gain support for his new Marijuana Justice Act.

A report published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence earlier this year showed that hospitalization rates for opioid dependence and abuse dropped by an average of 23 percent in states where pot was authorized for medicinal use. A 2014 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine also showed that the number of annual deaths from prescription opioid overdoses is 25 lower in states where medical marijuana use is allowed.

Earlier this week, the White House commission published a draft report citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating that 142 Americans die every day as a result of drug overdoses. The data also revealed that in 2015, close to two-thirds of drug overdoses were linked to powerful opioids like fentanyl, heroin, OxyContin and Percocet.

“The average American would likely be shocked to know that drug overdoses now kill more people than gun homicides and car crashes combined,” the report stated. “In fact, between 1995 and 2015, more than 560,000 people in this country died due to drug overdoses — this is a death toll larger than the entire population of Atlanta.”

Once seen as a problem that began on street corners, commission members argued that drug addiction is now manifesting in doctor’s offices and hospitals across the country. The group said it has taken a number of steps to combat the growing epidemic, from reaching out to governors’ offices across all 50 states for input to organizing listening sessions with treatment providers and addiction specialists.

Like Booker, Joe Shrank, co-founder of Los Angeles-based treatment clinic High Sobriety, believes that marijuana could help blunt (no pun intended) the number of opioid-related deaths — so much so that his facility encourages its patients to smoke weed as a part of their treatment.

“We know anecdotally, but with a lot of confidence, that it helps people with detox and it helps people stay off opiates,” Shrank told NBC News, adding that “Mary Jane” is deemed an “exit drug” by many of the center’s patients.

“If we’re dropping almost 100 bodies a day [due to the opioid crisis], we should be looking at all options,” Shrank continued. “If there are people who want to use cannabis to get off and stay off opioids … I’m, like, good with that. You’re not gonna drop dead. You’re gonna have chances in life.”

The White House commission on Monday set forth a list of recommendations for Trump to address the opioid crisis, the “first and most urgent” being for him to “declare a national emergency” either under the Public Health Service Act or the Stafford Act.

“Your declaration would empower your cabinet to take a bold step and would force Congress to focus on funding and empowering the Executive Branch even further to deal with this loss of life,” the commission wrote. “You, Mr. President, are the only person who can bring this type of intensity to the emergency, and we believe you have the will to do so and do so immediately.”

Other recommendations listed in the report included establishing and funding government incentives to increase access to Medicated-Assisted Treatment (MAT), mandated prescriber education initiatives to enhance prevention efforts and waiver approvals for all 50 states to eliminate barriers to drug treatment.

While the opioid epidemic is a serious issue, many leaders have pointed out the double standard when it comes to discussing and treating the opioid crisis vs. the crack epidemic of the late 80’s. California Sen. Kamala Harris (D) spoke on the issue during a talk at the Center for American Progress’ 2017 Ideas Conference earlier this year.

“Folks, let me tell you: These crises have so much more in common than what separates them,” Harris told conference-goers, pointing to a series of headlines that illustrated stark differences between the way people addicted to crack — who were often characterized as Black — were described, compared to how the media now discusses opioid users, who are largely described as white.

In recent years, certain cities and states have seemingly pulled out all stops to help those suffering from opioid addiction.

In July, the city of Buffalo, N.Y., began experimenting with the nation’s first opioid crisis intervention court, which would get users into treatment within hours of their arrest, the Associated Press reported. Users would then be required to check in with a judge every day for a month instead of once a week and adhere to a curfew.

In stark contrast, crack users in the late 1980s and early ’90s were treated with much less compassion, as stringent laws enacted as a part of the war on drugs tore families apart and landed thousands of African-Americans behind bars with no option for treatment.

Since then, there has been little policy action aimed at ending the opioid crisis, however. The only major bill approved by Congress on the epidemic appropriated $1 billion to drug treatment over two years, according to Vox. This falls way short of the tens of millions of dollars studies suggest the crisis actually costs the nation each year.

“Crises in a nation of 300 million people don’t go away for $1 billion,” Stanford University drug policy expert Keith Humphreys told the news site, referring to the 21st Century Cures Act funding. “This is the biggest public health epidemic of a generation.

“Maybe it’s going to be worse than AIDS. So, we need to go big.”