Washington D.C. police have increased alerts for missing children, which have been mostly Black and nonwhite.

Last week, NewsOne Now investigated recent reports of missing Black girls in Washington D.C. Host Roland Martin clarified how history validates Black concern, suspicion and rage regarding the safety of Black children. “Many of us, we came of age in the late ’70s and ’80s and remember what happened in Atlanta with African-Americans coming up missing,” Martin said.

Between 1979 and 1981, Atlanta, Ga., was under an international microscope when 29 Black people, mostly male teens and young boys, were murdered or never found. The case inspired a four-hour television miniseries starring James Earl Jones and Morgan Freeman, a book, “Evidence of Things Not Seen,” by acclaimed author James Baldwin and a $400,000 reward pledge from late boxing icon Muhammad Ali. A Black male, Wayne Williams, was found guilty of killing two adults, assumed to be the culprit in the other 27 cases and has remained incarcerated for over three decades. No one was ever convicted or even charged for Atlanta’s missing and murdered Black children.

Washington’s Metropolitan Police Department staunchly rejects the notion of a similar predator(s) abducting Black teens in the nation’s capitol. They point to data indicating there is no escalation in missing teenagers and, according to NPR, “instead contend that the public perception of an increase is actually a product of their more dedicated push to publicize these cases.” As of March 29, The New York Times reported 18 open cases of missing juveniles in the district, all of them nonwhite.

Washington has not replicated Atlanta’s torture of discovering the discarded corpses of Black children. However, the near symmetry of these events confirms the appalling vulnerability confronting generations of Black children.

Known respectively as “Chocolate City” and “The Black Mecca,” Washington D.C. and Atlanta are renown for their large Black populations. Although “gentrification” has banished a growing number of the district’s Black residents, both cities tout progressive legacies of electing Black officials to public office. Atlanta showcased its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, during the years of the missing and murdered children. Civil rights veteran Julian Bond was a Georgia state senator representing a district in Atlanta at the time of the crisis. Washington currently has a Black mayor, Murial Bowser, and a Black delegate to Congress, Eleanor Homes Norton. Police departments in both cities employee a hefty number of Black officers.

None of this was sufficient to safeguard Black children.

In fact, many Atlantans and Washingtonians allege that even in major metropolises with high-ranking Black officials, protection of Black children is rarely a top priority.

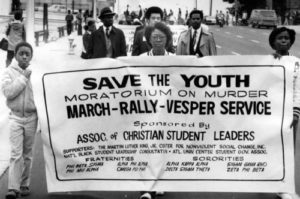

In 1981, more than 100 people marched through downtown Atlanta in response to the murdered and abducted Black children.

Leanita McClain, the first Black member of the Chicago Tribune editorial board, chronicled the 1981 response to the Atlanta horrors: “There were marches across the country, celebrity benefit concerts and charges that police weren’t trying hard enough, that no one cared because the children were Black.”

Julia Craven’s coverage of D.C.’s missing Black girls suggests we flunked history and are repeating trauma. Black and other nonwhite children remain “less likely to return home, more likely to be written off as runaways and often don’t get as much media attention when foul play is suspected,” writes Craven. Data from the Black and Missing Foundation indicates 36.8 percent of missing children in the U.S. are Black, although our overall population is only 13 percent of the country. Craven underscores this “relative lack of coverage also helps perpetuate the myth that Black and brown girls aren’t victimized.” And if they should receive media attention, Black children are often portrayed as promiscuous, delinquent and unworthy of rescue.

Speaking with Washington’s Mayor Bowser, Roland Martin declared a crucial element of the missing children of Atlanta and D.C. is the sexual exploitation of Black children.

Chet Dettlinger is a former Atlanta police officer who privately investigated the missing Black children during the ’80s. He co-authored a book, “The List,” describing his involvement and theories on the case. Dettlinger found sufficient evidence that a number of the missing and murdered youths were victims of child prostitution and speculated that a child prostitution ring might have been in operation in Atlanta. The missing and murdered Black children may have represented the permanent dissolution of a child sex trafficking operation.

Bowser and the Washington police maintain there’s no evidence that D.C.’s missing Black girls are victims of sexual trafficking. Parents and concerned residents are not convinced. During a recent town hall in Southeast Washington’s Ward 8, home to many of the missing Black girls, Acting Police Commissioner Peter Newsham was asked to define human trafficking and to respond to allegations that police officers may be involved in this criminal enterprise. The Final Call reports, “Things got heated, especially when the community members reminded police of a former officer [Linwood Barnhill Jr.] arrested and convicted for prostituting teen girls.”

Phylicia Henry, the director of the district’s Courtney’s House, a nonprofit organization to support victims of sex trafficking, attended the town hall and does not share Newsham’s opinion. She told a radio audience, “The majority of those kids on the missing police report released from MPD were referred to us or are currently in our program. So, here at Courtney’s House, we know that sex trafficking is behind these missing kids.”

Black D.C. residents and lawmakers are working diligently to cease any resemblance to Atlanta’s history. Bowser launched a new task force to determine what resources are needed to support at-risk youth. The Associated Press reports that Congressional Black Caucus chairman Cedric Richmond and Delegate Norton formally asked Attorney General Jeff Sessions to “devote the resources necessary to determine whether these developments are an anomaly or whether they are indicative of an underlying trend that must be addressed.”

Perhaps the outrage and awareness caused by the #MissingDCGirls social media blitz will help terminate what Penn State professor Jonathan Eburne describes as Black children being “heirs not merely to the immediate terror of a lone serial killer but to a long and systematic legacy of violent disappearance.”

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.