The Afro-American Patrolman’s League was formed in 1968 in response to the discriminatory mistreatment of Black residents and police officers in Chicago. Image courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

In an effort to add context to the ongoing debate over policing in the U.S., Chicago’s Museum of History has unveiled a series of documents, photos and memorabilia on an African- American police league that formed in the late 1960s.

Artifacts related to the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, a police organization dedicated to improving the standards of police performances in Black communities, were made accessible to the public through the museum’s Research Center last week. As the U.S. struggles to deal with discriminatory policing in majority-Black communities and the numerous fatal shootings of African-Americans by police, museum curators thought it appropriate to unveil documents from a time when tensions between law enforcement and Black abd brown communities nearly boiled over.

“Given continuing concerns about policing in Chicago, especially as it relates to Black and brown communities, the papers of the [police league] illuminate how the past matters now,” said Joy Bivins, director of the museum’s curatorial affairs. “This collection also shows the possibility and value of police and communities working together to address those concerns.”

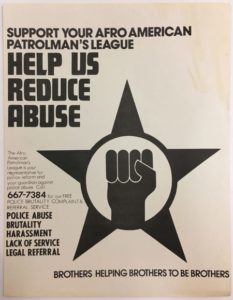

Also featured at the museum are fliers posted by the group urging local residents to report police abuse, along with logbooks and other documents tracking instances of police brutality, according to DNAInfo.com.

Founded by Officer Edward “Buzz” Palmer and four other Chicago officers in May 1968, the AAPL set its goals “to elevate the image of the Black policeman to a position of dignity and respect, especially in the Black community; to work for total police reform; and to strive for improved relations between Black and white policemen,” papers featured in the museum’s collection stated. The group also was created in response to the mistreatment of Chicago’s African-American residents by police, leading members to educate locals about the criminal justice system and ways to protest the abuses of police authority.

Image courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

Black America Web reported that Palmer and the organization’s other founders — Curtis Cowsen, Wilbur Crooks, Jack Debonnett and Renault “Reggie” Robinson — were often outspoken about these issues, which angered their white counterparts. This tension reportedly led to retaliation and abuse from the white officers, who saw the creation of the AAPL as an affront to the CPD.

The Department fought tooth and nail against the development of the organization, which later prompted the AAPL to file a discrimination suit in 1973 accusing the CPD of relegating its African-American officers to a lower status and passing them up for promotions often in favor of white officers. Their case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in its favor and is considered a landmark case that addressed the slow integration and practices of police stations across the nation, according to Black America Web.

Now known as the African-American Police League, the group joined similar police organizations to later form the National Black Police Association.

“African-American police officers have made tremendous gains since 1968,” wrote volunteer Robert Blythe in a blog post for the museum. “Nevertheless, many of the issues identified by the [police league] remain active concerns, and the organization’s papers could not be more relevant today.”