Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy and a phalanx of armed white supporters. Las Vegas Review-Journal, John Locher/AP Photo

The first Women’s March on Washington, which was the day after the inauguration of Donald J. Trump, attracted nearly a half million people and inspired solidarity marches in cities throughout the country and internationally. The historic event was directly influenced by the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington. According to the Los Angeles Times, the Women’s March organizers cherry-picked a name that would evoke “Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights march.” One would think that a half-century earlier, Dr. King and other Black freedom fighters were cordially welcomed to the nation’s capitol to redress their racial grievances.

Maximum revisionist history.

March on Washington attendee and former Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X repeatedly testified about the white trepidation in advance of “milling angry Blacks” invading Washington. Susan McBee’s July 4, 1963, Washington Post report, published just over a month before the iconic protest, corroborates Malcolm X. In “Feared March on Hill Might Backfire,” McBee documented white anxieties about the “Negro demonstration,” in addition to accusations “that Negroes were trying to intimidate Congress” into passing civil rights legislation. Dr. King, an eventual Nobel Prize winner, and Georgia Congressman John Lewis, who spoke at the ’63 march and earlier this month was maligned by President Trump as being “all talk, no action,” were both Trayvon Martins. Unarmed. Threatening. Black.

The difference between these two pilgrimages for justice reveals a primary commandment of white supremacy: Only white people are allowed to be mad. Assassinated Muslim minister Malcolm X concluded that when people “get angry, they bring about a change.” White culture simultaneously projects images of white fury, white violence, while suppressing and scolding any evidence of justified Black rage.

“Black rage is founded on two-thirds a person.

Raping and beatings and suffering that worsens.

Black human packages tied up in strings.

Black rage can come from all these kinds of things.”

— Ms. Lauryn Hill, from “Black Rage”

The difference between how white and Black indignation is mitigated is most obvious when the enraged individual is armed. A hodgepodge of white activists, and even criminals, is afforded the luxury of broadcasting its wrath while flaunting a firearm and living to tell about it. Black citizens are forced to holster their constitutional rights to hold a gun or a grievance.

In 2009, weeks after Barack Obama was inaugurated as president, gun-toting white citizens stormed town hall meetings across the country, ostensibly voicing their divergent opinion on proposed health care reforms. NPR’s E.J. Dionne Jr. described them as a “minority engaging in intimidation backed by the threat of violence.” Dionne contextualized the firearm’s history of enforcing white power and labeled it “profoundly troubling that firearms should begin to appear with some frequency at a president’s public events only now, when the president is Black.”

These New Age gunslingers prompted many news outlets to provide civics lessons on federal and state gun laws, but nearly all neglected to include the history of statutes designed to deny Black citizens firearms. In “Birth of a White Nation,” sociology professor and admitted racist Jacqueline Battalora details how colonial “Virginia lawmakers passed an enactment blocking … free Blacks from possessing any weapon including a club, gun, powder or shot. These laws combined to render persons of African descent all but completely self-defenseless, especially against violence inflicted by a ‘white’ person.”

Attorney and gun rights advocate Evan Nappen concedes there is an ongoing codification of laws to ensure a docile Black population. “Institutional racism in our gun-control laws is rampant. It goes back to the post-Civil War era, when the laws were passed to keep Black people and American Indians from arming themselves.”

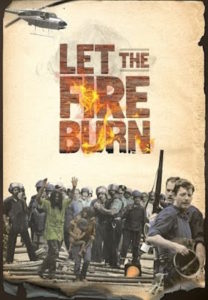

“Let The Fire Burn” is Jason Oder’s film on the 1985 bombing of the Philadelphia MOVE residence.

Meanwhile, no such legislation exists to keep the Cliven Bundys of the world from obtaining a pistol. The Oregonian reports the 70-year-old, white Nevada rancher is facing charges of conspiracy, obstruction, weapons violations and “assault offenses against federal officers” for his 2014 armed confrontation with Department of Justice agents. Officers didn’t fire a single shot at Bundy and his armed, white conspirators.

Jason Osder is a George Washington University professor and director of the documentary, “Let The Fire Burn.” The film examines the 1985 assault on the Philadelphia, Penn., MOVE organization, a predominantly Black group opposed to racism and all forms of oppression. MOVE advocated self-defense and publicly brandished guns. Philadelphia police bombed their house, killing 11 people, including five children. The fire incinerated the MOVE residence and the neighboring 60 houses, which were exclusively Black owned. Osder’s examination of the MOVE tragedy debuted on PBS within days of the Bundy conflagration in the Nevada desert. When asked to contrast the two events, Osder admitted the inconceivability of Whites affording a Black Cliven Bundy the same nonviolent, nonlethal treatment.

Cliven Bundy’s white life and white anger matters.

Conversely, when Black people organize to guard and value Black mothers and Black children, they’re assailed as a terrorist threat. In December 2016, Jacqueline Craig, a Black mother in Texas, was shackled, detained on the ground and then arrested by local police after she confronted a white neighbor who admitted assaulting her 7-year-old son. The neighbor was not handcuffed or arrested. Atlanta Black Star’s Rick Riley reports that earlier this month, a group of “two or three armed [Black] men carrying assault rifles” patrolled the area where Ms. Craig and her son were violated. In less than a half hour, local police rendered “the persons of African descent all but completely self-defenseless.” Unlike the white, armed “Obamacare” opponents or Cliven Bundy, the Black patrollers were disarmed, handcuffed and forced to lie prone on the ground.

Justin Tinsley’s masterful review of Solange Knowles’ “A Seat at the Table” references one of late comedian Richard Pryor’s recurring thoughts: “It’s often you wonder why a n—er don’t go completely mad.” Knowles’ concluding verse on the standout track “Mad” provides the answer: “Man, this s–t is draining. But I’m really not allowed to be mad.”

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.