By Jacqueline Bediako

Immigrants are good-for-nothing toilet cleaners and ice cream sellers. They should all go back to where they came from—or so this is what the stereotype implies. As the daughter of a Ghanaian immigrant who decided that the future of her children was more important than her own life, I am in a position to testify about the enduring strength of immigrants. If we want to be educated about how to remain “optimistic” or develop the trait called “resilience,” we must look to immigrants for our education.

Immigrants, both from Africa and the diaspora, must occupy podiums in lecture halls and tell us what it means to love unconditionally. They must teach us about the art of remaining dignified, despite rejection on a mass scale. We must vigorously take notes and find comfort in the wisdom of immigrants who can teach us so much about humanity. Indeed, immigrants have an insight that is omniscient in nature – because it is an insight that reaches into the darkness of the future—and ponders a better existence for unborn children.

So when I referred to stereotypes about immigrants in my last article, A Black British-Ghanaian Living in US Realizes Her Accent Won’t Protect Her From Police Abuse and Stereotyping, I did this for two reasons: to convey that immigrants are more than what these stereotypes divulge, and to show that African-Americans, like immigrants, are falsely assigned to categories.

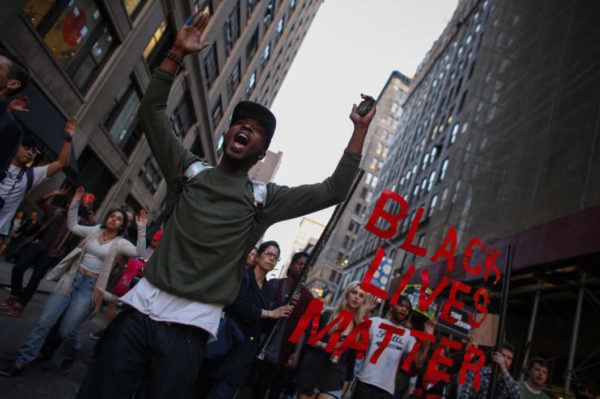

There are parallels to be drawn between the African-American struggle and the African immigrant struggle because when one endures suffering to an unbearable degree, or views death as an imminent consequence, boarding an overloaded ship—which many would view as dangerous and obscene—becomes the only rational choice. And when a member of one’s community has his spine severed in police custody, and is dead a week later with no explanation, taking to the streets to release a public display of outrage becomes rational and necessary. You cannot beat me, rape me and shower me with my own blood and not expect a reaction. You cannot slowly hammer me into the depths of inferiority, rip my baby from my womb, and not expect me to convulse and scream.

Indeed, rebellion often comes after a prolonged period of restraint—every human being can be pushed to breaking point. This breaking point has arrived, and it lives in the form of a revolutionary uprising, an uprising that the world can see playing out on the streets of Baltimore.

In the spirit of unity, I should be in Baltimore linking arms with my African-American brothers and sisters, holding my piece of card with #Freddie Gray chipped into it, and demanding the reform of a system which balances on the heels of white supremacy. It’s unacceptable for us to be slaughtered at the hands of police, and we must protest as one collective mass of Black people.

We will not lie down and allow ourselves to be whipped repeatedly by a criminal justice system that perpetuates the horror of the school-to-prison pipeline. Enough is enough. We will not work tirelessly to complete college degrees only to face unemployment and discrimination at disproportionate rates. Enough is enough. We will not accept anything substandard— substandard housing, substandard schools, substandard healthcare, substandard transport links. Enough is enough. We will not abide by the rules of a defective police department, which has the audacity to let cops pay-to-play, frame us for crimes we did not commit and take the lives of our sons, fathers and brothers. Enough is enough. I say “we” because as Black people, we must stand together.

My mother arrived in the UK as a multilingual, intelligent and resourceful woman only to experience the shame and suffering induced by poverty and racism. Institutional racism, which I acknowledge continues to exist in the UK, creates social and economic barriers to immigrant success, and it deeply affected my mother’s quality of life. I refer to myself as a Black British-Ghanaian because my mother sacrificed so much to have children who were educated in the English system. I take full ownership of the “Black,” “British,” and “Ghanaian” labels because each label functions simultaneously as an invaluable gift from my mother, and as a reminder of her struggle. And to the white person protected by “privilege,” and all the amenities that come with that label, do not label me a “thug” because I protest injustice when you have not made the effort to examine the context from which my behavior derives.

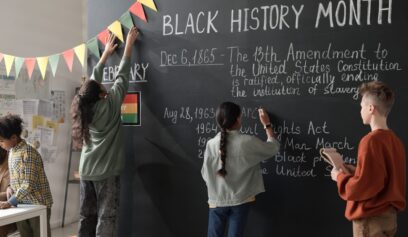

I am the living embodiment of my mother’s dream, and soon I will have many letters after my beautiful last name. Each group of letters will symbolize the credentials I have amassed as the daughter of an immigrant. And for both African immigrants and African-Americans, education is of great value. According to Nelson Mandela, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” I believe there is Black girl in Chicago who is the reincarnation of a former me, spending time in her room with her nose between books, hoping that one day she will become a published writer.

To the few who called me a Black foreigner, you should recall the work of Malcolm X. Malcolm X was killed for many reasons, including his belief in the international union of Black people. To ensure that Malcolm X’s death was not in vain, we should adopt the Pan-Africanist ideology. Similarly, activist Stokely Carmichael called for Pan-African unity and was influenced by political mentors including exiled Ghanaian president, Kwame Nkrumah who himself was influenced by the Honorable Marcus Garvey.

To uphold the principles of Pan-Africanism, African-Americans should support Malian immigrants escaping poverty and corruption, and in the same breath continue to fight the poverty experienced by Black residents in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Black people in New York City dealing with the social and economic pressures caused by gentrification should connect with Black people in London, also facing the instability triggered by gentrification.

Finally, some questioned why I failed to acknowledge Black success stories. According to them, not every Black person in America is living an American Nightmare. I hear you, there are lots of successful Black people in America—more power to them. But the stories of Black people who are incarcerated, victimized, or murdered must be told. While I will touch on Black success stories in my writing, I am primarily here to bring attention to the oppressed.

Although our experiences in the countries we live in are unique and context-dependent, it doesn’t mean parallels cannot be drawn. Consequently, the power of collective action at a global level is not to be underestimated. From Accra to Atlanta, from Bamako to Baltimore, immigrant or citizen, Black people must stand together.

Jacqueline Bediako is a writer, teacher and activist currently living in Brooklyn, New York. She describes herself as a Black British-Ghanaian, and has called New York City home for the past seven years. Jacqueline’s work focuses on race, politics, immigration, and the education of students with disabilities. Follow her @jb2721.